The Chrome Dev Summit concluded earlier this week. Announcements and discussions on hot topics impacting the greater web community at the event included Google’s Privacy Sandbox initiative, improvements to Core Web Vitals and performance tools, and new APIs for Progressive Web Apps (PWAs).

Paul Kinlan, Lead for Chrome Developer Relations, highlighted the latest product updates on the Chromium blog, what he identified as Google’s “vision for the web’s future and examples of best-in-class web experiences.”

During an (AMA) live Q&A session with Chrome Leadership, ex-AMP Advisory Board member Jeremy Keith asked a question that echoes the sentiments of developers and publishers all over the world who are viewing Google’s leadership and initiatives with more skepticism:

Given the court proceedings against AMP, why should anyone trust FLOC or any other Google initiatives ostensibly focused on privacy?

The question drew a tepid response from Chrome leadership who avoided giving a straight answer. Ben Galbraith fielded the question, saying he could not comment on the AMP-related legal proceedings but focused on the Privacy Sandbox:

I think it’s important to note that we’re not asking for blind trust with the Sandbox effort. Instead, we’re working in the open, which means that we’re sharing our ideas while they are in an early phase. We’re sharing specific API proposals, and then we’re sharing our code out in the open and running experiments in the open. In this process we’re also working really closely with industry regulators. You may have seen the agreement that we announced earlier this year jointly with the UK’s CMA, and we have a bunch of industry collaborators with us. We’ll continue to be very transparent moving forward, both in terms of how the Sandbox works and its resulting privacy properties. We expect the effort will be judged on that basis.

FLoC continues to be a controversial initiative, opposed by many major tech organizations. A group of like-minded WordPress contributors proposed blocking Google’s initiative earlier this year. Privacy advocates do not believe FLoC to be a compelling alternative to the surveillance business model currently used by the advertising industry. Instead, they see it as an invitation to cede more control of ad tech to Google.

Galbraith’s statement conflicts with the company’s actions earlier this year when Google said the team does not intend to disclose any of the private feedback received during FLoC’s origin trial, which was criticized as a lack of transparency.

Despite the developer community’s waning trust in the company, Google continues to aggressively advocate for a number of controversial initiatives, even after some of them have landed the company in legal trouble. Google employees are not permitted to talk about the antitrust lawsuit and seem eager to distance themselves from the proceedings.

Jeremy Keith’s question referencing the AMP allegations in the recently unredacted antitrust complaint against Google was extremely unlikely to receive an adequate response from the Chrome Leadership team, but the mere act of asking is a public reminder of the trust Google has willfully eroded in pushing AMP on publishers.

When Google received a demand for a trove of documents from the Department of Justice as part of the pre-trial process, the company was reluctant to hand them over. These documents reveal how Google identified header bidding as an “existential threat” and detail how AMP was used as a tool to impede header bidding.

The complaint alleges that “Google ad server employees met with AMP employees to strategize about using AMP to impede header bidding, addressing in particular how much pressure publishers and advertisers would tolerate.”

In summary, it claims that Google falsely told publishers that adopting AMP would enhance load times, even though the company’s employees knew that it only improved the “median of performance” and actually loaded slower than some speed optimization techniques publishers had been using. It alleges that AMP pages brought 40% less revenue to publishers. The complaint states that AMP’s speed benefits “were also at least partly a result of Google’s throttling. Google throttles the load time of non-AMP ads by giving them artificial one-second delays in order to give Google AMP a ‘nice comparative boost.‘”

Although the internal documents were not published alongside the unredacted complaint, these are heavy claims for the Department of Justice to float against Google if the documents didn’t fully substantiate them.

The AMP-related allegations are egregious and demand a truly transparent answer. We all watched as Google used its weight to force publishers both small and large to adopt its framework or forego mobile traffic and placement in the Top Stories carousel. This came at an enormous cost to publishers who were unwilling to adopt AMP.

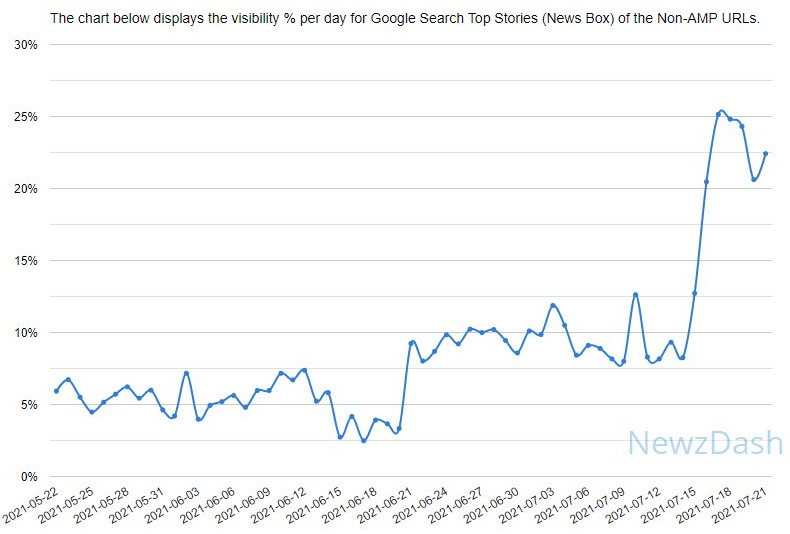

Barry Adams, one of the most vocal critics of the AMP project, demonstrated this cost to publishers in a graph that shows the percentage of articles in Google’s mobile Top Stories carousel in the US that are not AMP articles. When Google stopped requiring AMP for the mobile Top Stories in July 2021, there was a sharp spike in non-AMP URLs being included.

Once AMP was no longer required and publishers could use any technology to rank in Top Stories, the percentage of non-AMP pages increased significantly to double digits, where it remains today. Adams’ article calls on the web community to recognize the damage Google did in giving AMP pages preferential treatment:

“But I’m angry. Because it means that for more than five long years, when AMP was a mobile Top Stories requirement, Google penalised these publishers for not using AMP.

There was no other reason for Google to stop ranking these publishers in their mobile Top Stories carousel. As is evident from the surge of non-AMP articles, there are likely hundreds – if not thousands – of publishers who ticked every single ranking box that Google demanded; quality news content, easily crawlable and indexable technology stack, good editorial authority signals, and so on.

But they didn’t use AMP. So Google didn’t rank them. Think for a moment about the cost of that.”

Even the publishers who adopted AMP struggled to get ad views. In 2017, Digiday reported on how many publishers have experienced decreased revenues associated with ads loading much slower than the actual content. I don’t think anyone at the time imagined that Google was throttling the non-AMP ads.

“The aim of AMP is to load content first and ads second,” a Google spokesperson told Digiday. “But we are working on making ads faster. It takes quite a bit of the ecosystem to get on board with the notion that speed is important for ads, just as it is for content.”

This is why Google is rapidly losing publishers’ trust. For years the company encumbered already struggling news organizations with the requirement of AMP. The DOJ’s detailed description of how AMP was used as a vehicle for anticompetitive practices simply rubs salt in the wound after what publishers have been through in expending resources to support AMP versions of their websites.

Automattic Denies Prior Knowledge of Google Throttling Non-Amp Ads

In 2016, Automattic, one of the most influential companies in the WordPress ecosystem, partnered with Google to promote AMP as an early adopter. WordPress.com added AMP support and Automattic built the first versions of the AMP plugin for self-hosted WordPress sites. The company has played a significant role in driving AMP adoption forward, giving it an entrance into the WordPress ecosystem.

How much did Automattic know when it partnered with Google in the initial AMP rollout? I asked the company what the precise nature of its relationship with Google is regarding AMP at this time.

“As part of our mission to make the web a better place, we are always testing new technologies including AMP,” an official spokesperson for Automattic said.

This may be true but Automattic has done more than simply test the new technology. In partnering with Google, it has been instrumental in making AMP easier for WordPress users to adopt.

“We received no funds from Google for the project,” a spokesperson for Automattic said when asked if the company was compensated as a partner in this effort.

What did Google promise Automattic to convince the company to become an early partner in the AMP rollout? I asked if the company has an official response to the allegations that Google was throttling the load time of non-AMP ads by giving them artificial one-second delays in order to give Google AMP “a nice comparative boost.” The spokesperson would not respond to the specific claims but indicated the company did not have prior knowledge of any actions that might not be above board:

We chose to partner with Google because we believed that we had a shared vision of advancing the open web. Additionally, we wanted to offer the benefit of the latest technology to WordPress users and publishers including AMP.

While we aren’t able to comment on legal matters in progress, we can say that over the course of our partnership, we were not aware of any actions that did not align with our company’s mission to support the open web and make it a better place.

The antitrust complaint also details a Project NERA, which was designed to “successfully mimic a walled garden across the open web.” When asked about this, Automattic reiterated its commitment to supporting the open web and gave the same response: “We were not aware of any actions that did not align with our company’s mission.”

In examining the weight of the DOJ’s allegations, it’s important to consider how this impacts WordPress as a CMS that is used by 42% of the web. A new performance team for WordPress core is being spearheaded by Yoast and Google-sponsored employees. The initial proposal is to improve core performance as measured by Google’s Core Web Vitals metrics. These metrics are a set of specific factors that Google deems important for user experience.

Without questioning the personal integrity of the contributors on that team, I think it’s important that Google leadership acknowledge how AMP has damaged publishers’ trust in light of recent events. Many of these contributors are heavily involved in building AMP-related resources for the WordPress ecosystem. Are their contributions purely aimed at making WordPress core more performant or is there a long game that serves Google’s interests being woven into this initiative? Would these employees even be aware of it if there were?

These are important considerations if Google defines the performance metrics WordPress is measuring against. The company’s alleged misdeeds seem to be buried high up in the command chain. Those tasked with peddling AMP may have had no knowledge of the alleged anticompetitive practices identified by the DOJ in Google’s internal documents. The WordPress community should continue to be vigilant on behalf of publishers who depend on WordPress to remain an unadulterated advocate for the open web.